February 24, 2017

Two commonly held premises fail when applied to the purchase of vaccines. First, that public procurement is transparent; second, that the richer a country is, the more it pays pharmaceutical companies for each dose. Neither of them is wholly fulfilled when we talk about the relationship between sellers and governments.

The opacity of the sector permeates even the World Health Organization (WHO), which publishes a database of vaccine prices paid by various governments, but keeps their names hidden at the request of the member states themselves. No one wants to be singled out if they obtain better of worst prices than their neighbour, nor fail to comply with the confidentiality agreements signed with the pharmaceutical companies.

That is why many countries prefer not to publish such data. But, despite the general opacity, there are exceptions. Nations in which their official procurement web sites offer, most often hidden in bid specifications and scanned contracts, information on the purchase price of each dose. For this investigation, we analyze this exceptional data from seven countries (Why only seven? How have they been chosen?), together with three international organizations: Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF); Unicef, which serves as a central purchasing point for initiatives such as GAVI, an alliance to provide vaccines to the world’s poorest countries; and the Revolving Fund of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), a joint purchasing system used by 41 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Per dose prices paid per governments

€

There can be price differences due to brand, packaging (vial or syringe), strains or volume, among others. PAHO data is made of weighted averages, i.e. it’s not broken down by manufacturer. For the rest, we include all the data found. Methodology

Brand new and expensive

As with drugs, new products and their patents drive prices up. “With only two manufacturers for each of the new and much more expensive vaccines –PCV [pneumococcal], rotavirus and HPV [Human Papilloma Virus]– and the inability to use the two available products interchangeably, companies are enjoying near monopolies,” denounces MSF in a report focusing entirely on the global vaccine market.

Two laboratories produce the vaccine against the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), which causes cervical cancer, among other: Merck (with Gardasil) and GSK (with Cervarix). The United States government purchases the most advanced version of Gardasil, which protects against nine types of virus, at a price of between €109.58 (adults) and €125.65 (preteens) each dose. Merck sells its version against four HPV types at €22 to Portugal and €14.5 to MSF. While GSK sells Cervarix, which protects against two types, to the PAHO Revolving Fund for about eight euros, a price that, although much lower than that obtained by the member countries on their own, prevents many of them from including the vaccine in their immunization programs.

Spain: same price for different vaccines

Spain tendered the purchase of the HPV vaccine with a requirement: it should protect against at least two types of virus. Both laboratories bid and both offered the same price, the maximum allowed, without any rebates, despite their vaccines being different compositions: €31.02 per dose.

Pneumococcus is a microorganism that causes pneumonia and meningitis. The 13-valent vaccine, produced by Pfizer and GSK, is one of the most expensive. Pfizer’s version ranges from €113.54 in the United States to €42.85 and €45.73 in Spain and Portugal, very similar prices for two countries separated by more than 6,000 euros in per capita GDP. And these figures must be multiplied by three, the number of doses needed to immunize each child. GAVI countries can access it at a lower cost, €6,58 euros per dose, but organizations like Médecins Sans Frontières and many middle-income countries are left out. In fact, in Idomeni (Greece) MSF had to pay around €60 per dose to vaccinate refugees. Due to its hight price, this is the only vaccine for which MSF made an exception to its policy of not accepting donations.

Why doesn’t MSF accept donations?

“Free is not always better.” That’s the conclusion of an article by Médecins Sans Frontières in which the organization explains why it rejects donations of vaccines. Four reasons are given: 1) donations are usually accompanied by restrictions, for example on which areas or populations can be used, which can delay vaccination in emergency campaigns; 2) donations can put an end to efforts to increase access to affordable vaccines by removing incentives for competitors to enter a market where free vaccines are available; 3) donations are used as a justification for why prices remain high for others, including humanitarian organizations and developing countries; and, finally, 4) donations can disappear as quickly as they arrived.

Because of these new and more expensive vaccines, the cost of immunizing a child has multiplied by 68 between 2001 and 2014, according to the organization.

How are vaccine prices set? There are two ways. The first is based on costs, that is, the vaccine is priced according to how expensive it was to produce. As with other medicines, pharmaceutical companies and organizations disagree about the real cost of developing a new vaccine. The second, and most common, is linked to how much buyers can or are willing to pay. This is tiered pricing, which means that the richer a country is, the more it pays, and is the system advocated by manufacturers, according to the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries.

We can see how tiered pricing works for the MMR -against measles, mumps and rubella- or Hepatitis B vaccine, whose prices rise together with a country’s income. But the theory does not always match reality. While several variables -such as purchase volume or packaging type- may justify some differences, we can find trends in the data that don’t seem to fit the idea of richer buyers paying more.

Per capita GDP

The DTP vaccine has been part of vaccination schedules across the world for a long time. It protects against diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough, and has several versions. The advanced version (DTaP, with acellular pertussis) has less side effects and is more expensive than the original DTP. Despite huge differences in wealth between the United States and Spain -the former more than doubling the per capita GDP of Spain- both buy doses from GSK at a very similar price: €13.28 for Spain, €13.86 for the United States.

A third version is Tdap, a low dosage and also acellular vaccine, normally used for adults. In this case, the figures don’t make sense either. Poland pays more (€14.83) than Portugal (€13.21) and Spain (€8.85), despite the fact the three countries buy from the same provider, GSK, and that the order of their income levels is just the opposite.

The DTP vaccine is sometimes combined with others to try to provide as many immunizations as possible in one go. An example is the pentavalent vaccine which protects -on top diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis,- against polio and Hib (anti-Haemophilus influenzae type b, a bacterium that causes pneumonia, respiratory problems, infections and can lead to death). Ukraine (lower-middle income) pays Sanofi almost the same price as Spain (high income): more than €22 per dose. If we add the Hepatitis B vaccine to the previous combination we get the hexavalent vaccine. Both Portugal and Spain buy it from GSK, but the Portuguese government pays almost eleven euros more per dose.

For the vaccine that protects against polio (IPV), Hungary pays more than Spain. In Italy, the price per dose is different for two purchases, even though both bids are awarded to Sanofi and in the same year, 2016.

Portugal went as far as to pay, in early 2017, 25 euros per dose of the vaccine against tuberculosis (BCG), which has suffered from stockouts in recent years. Shortly before that, in 2016, the price had been just €8.90, even though, due partly to smaller volumes being purchased, Portugal’s price was much higher than those of the rest of the countries analyzed.

The number of variables that can affect the final price -fees, associated insurance, whether transportation costs are included, packaging, volume, differences of elaboration or composition…,- and the little or no information provided about them, makes exposing the ultimate causes of price differences challenging. But, even despite all these nuances, shedding light on how much each of these seven countries and three organizations is paying for each vaccine helps visualize the playing field and better understand its rules.

Joint purchasing systems

In most cases, the lowest market prices are those offered to Unicef, which runs a joint purchasing mechanism for developing countries. The organization consolidates purchases and charges a handling fee of between 3 and 4.5%, depending on the vaccine and the income level of the country (i.e. the 43 classified as least developed pay the lowest percentage).

The Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI), the result of a public-private partnership which finances vaccines for poor countries globally, buy its vaccines through Unicef. (Disclosure) Its weight is very important in the market: in 2015 they acquired more than 2,770 million doses for almost 1,721 million dollars. At the moment, 78 countries purchase their vaccines via GAVI. Countries with a per capita Gross National Income below a threshold predetermined by the organization, established at $1,500 in 2011 and updated since then according to inflation, are accepted. Those that l the requirements go through a transition period, during which their contribution to the purchase of vaccines goes up while the percentage that GAVI finances decreases gradually, until they become independent in five years.

Some of the lowest prices that UNICEF negotiates are only valid for countries part of GAVI or for those still transitioning, as is the case for the papilloma vaccine, available at between €4.23 and €4.32 per dose. In fact, these amounts are sometimes used as the lowest reference worldwide. Médecins Sans Frontières has criticized this system, since it leaves out middle-income countries that cannot afford newer and more expensive vaccines, and because humanitarian aid organizations can’t access these same discounts. MSF buys the DTP at twice the price of what Unicef gets, for instance.

In contrast to the GAVI model (targeted at the poorest countries), an alternative joint model has nothing to do with the capacity of states to acquire vaccines: the Revolving Fund of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). 41 countries and regions of Latin America and the Caribbean acquire their vaccines through this 40-year old system, which relies on economies of scale or, in more earthly terms, union makes force. “The Hepatitis B vaccine began costing $50, and now costs much less than a dollar. That is what is achieved with economies of scale,” explains Mario Martínez, who works in the Fund’s Guatemalan office.

Both systems are related. Both include clauses in their negotiations that establish that their prices must be lowered accordingly if a manufacturer sells to another organization or country at a better price. But pharmaceutical companies don’t like to offer the same conditions to both low-income countries and to other, more developed, members of the Fund, such as Brazil. Hence, PAHO was forced to make exceptions to their price matching rule for the most expensive vaccines: pneumococcal, rotavirus and HPV ones.

In some other instances, manufacturers offer different packaging to GAVI and the Fund, thus avoiding having to lower prices for all of Latin America. As an example, Sanofi sells GAVI a box of ten polio vaccine doses for €0.75 a dose, the lowest price in the world. But the PAHO Fund is not offered this presentation, only the one- and five-doses packages, where prices per dose are higher, and matching what Unicef would pay.

Per dose prices paid by organisations

€

For the countries participating in the Revolving Fund there is an extra benefit, beyond the price reduction: “I don’t have to handle money. The Government pays PAHO, and they bring me the vaccines. In terms of corruption, I feel I’m bulletproof,” celebrates Eduardo Suárez, director of the immunization program of the Ministry of Health of El Salvador, which adds: “This positive experience that Latin America has had should be transmitted to other regions.” Although there have been other attempts to set up joint purchasing systems across the world, none has been as fruitful and has had the weight of the Fund or GAVI. In 2014, the European Commission approved an agreement for the joint purchase of vaccines and other medical products. It has never been used.

“The path must be to unite all these mechanisms, not only from America, but from the whole world, so that all countries have equitable access to products like vaccines,” argues Mario Martínez from PAHO. And not just because of economies of scale. Both Unicef and PAHO publish their purchase prices, which, due to their large volume, improve the transparency of the global market. One note though: PAHO only publishes the weighted average cost of each vaccine, without breaking down the exact price paid to each manufacturer.

Trading blindly

The UK government procurement website hides the prices at which the British government acquires vaccines. If we access a contract for the purchase of the rotavirus one, for example, we can know what’s being bought and from whom, but not the amount. The bid details include a note where the total price and the price per dose should be displayed: “Redacted under section 43(2), commercial interests”. The English government applies one of the exceptions of its Freedom of Information Act, which excludes information whose publication “would, or would be likely to, prejudice the commercial interests of any person (including the public authority holding it).” The exemption applies to the purchase of vaccines, but not to many other sectors: e.g. we can easily see how much the government spent buying software for hospitals.

This case is no exception and neither is the limited application of transparency laws to public contracting. And so happens in many more countries. In the previous cases, the price is not published. In some others instances, the number of doses purchased is hidden, making it impossible to calculate the item cost and find out the conditions agreed with pharmaceutical companies. In most cases, no information at all is published about these contracts. They fall through the cracks that are the exemptions in national transparency regulations. They may as well not exist.

The vaccine market dodges the rules of transparency and publicity of public procurement that do affect other sectors

“Most pharmaceutical companies do not disclose their prices, and many force buyers to sign confidentiality clauses that prohibit the release of such information,” criticizes Médecins Sans Frontières in its report. And that opacity is a problem because, he continues, “without price comparison mechanisms, countries do not fully understand the vaccine market and can not know if they are paying an affordable price for their vaccines.”

Laboratories, on the other hand, do not welcome the existence of reference prices with which to compare. The European Federation of Pharma Industries and Associations (EFPIA) believes transparency must be focused on “providing at the same time evidence-based data on the safety and effectiveness of the producte” but not on how much the governments are paying: “Publishing the prices will not make a difference either in terms of boosting confidence or improving access. As with most health and other services, specific agreements are mostly confidential, allowing for competition among suppliers and differentiated pricing to meet the needs of each country”, argues Faraz Kermani, EFPIA Communications Manager.

In May 2015, the World Health Assembly issued a resolution in which, in addition to demanding more competition in a market marked by oligopolies, stated that “publicly available data on vaccine prices are scarce, and that the availability of price information is important for facilitating Member States’ efforts towards introduction of new vaccines.”

The solution to this opacity, from the WHO itself, was to launch the V3P (Vaccine Product, Price and Procurement) project, a public comparison system for vaccine prices. The database enables users to visualize, for example, the huge price differences among manufacturers for identical or similar formulas, or the evolution of what governments have paid over the last few years. Countries submit information on a voluntary basis on the prices through which they’ve purchased the doses. 51 have sent data for 2015, a figure in which Europe is over-represented, with 30 of them.

If the number of countries contributing data continues to grow, this could be the solution to the opacity of the sector and, therefore, the end of blindfolded negotiations between governments and laboratories. It could, and is an important first step. But there is a limitation. When comparing between countries, V3P contains information on the region each country is located and which income category it belongs to (i.e. high, upper middle, lower middle or low), but it hides an important fact: the name of the country, which is replaced by an anonymised code. Thus, the platform created to promote more transparency in the sector through country comparatives does not allow direct comparisons between countries.

“We don’t say names will be never published, but at the moment we focus on increasing participation,” says Stephanie Mariat, head of the V3P, that explains that withholding the names was a demand from the countries themselves -but wouldn’t answer which ones in particular: “Some of our member states want to avoid finger pointing in case they pay particularly low or high prices. Also, some countries face confidentiality challenges and might decide to withdraw the publication of their prices if the country names were published.”

In addition, she argues that “having information about the location of the country (region), volumes, indication of income level and GAVI-eligibility (all being factors that can influence prices) brought enough information to a country to compare itself and use information coming from similar/peer countries”. She adds: “The name of the country does not bring more information when looking at the factors that influence prices.”

But in fact it does, since the price ranges within each income level category are very large. And one can’t just compare Poland with Greece, Germany or the United States (all of them in the same income category: high), the same way one can’t ignore the differences between Brazil, China, Bosnia, and Iraq, all upper middle income countries.

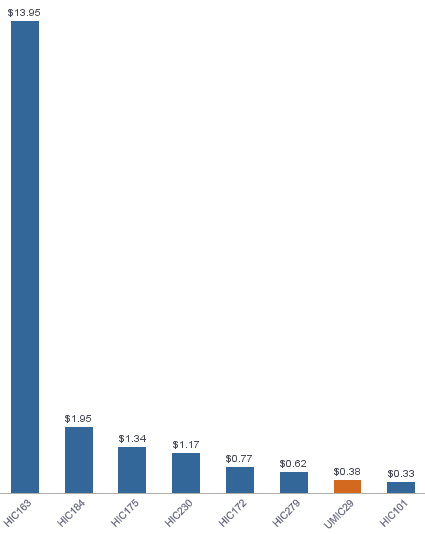

Proof of this are the large differences between countries in the same income level purchasing, for example, the tuberculosis vaccine sold by the Statens Serum Institute. The V3P data for seven high income countries shows prices going from as little as $0.33 to up to $13.95. How does this help a buyer demand a fair price when negotiating with pharmaceutical companies?

Alongside these seven countries, V3P data shows an anonymous country which, although poorer -it’s classified as upper middle income,- pays more per vaccine dose than one of the high income ones. Even if we’re still in the dark, and can’t know which countries the data refers to, this difference shows, once again, that not always the poorest buyers pay less.

Javier de Vega, Miguel Ángel Gavilanes and David Cabo collaborated in the data mining and review of this investigation. The data visualizations are by Raúl Díaz Poblete. More information, here.