March 2, 2017

Cervical cancer is the only 100% preventable cancer. Screening techniques can detect a precancerous lesion and eliminate it before the disease develops. For some years now, medicine has been able to get closer to the root: there is a vaccine to prevent papilomavirus, which causes this and other types of cancer. But cultural and social reluctance and high costs are slowing its deployment.

In 2015, more than 278,000 women worldwide died of cervical cancer. In 41 countries around the world, it’s the cancer that causes the most deaths among women, despite the ability to prevent each and every one of these cases. The vaccine is relatively new, but the screening systems that detect a cervical lesion in time not so much. For screening to work, it’s necessary for all women to undergo gynecological checks regularly, which is not the case in countries with resource and infrastructure problems. This is one of the reasons the highest numbers of cervical cancers occur in poor countries.

From HPV to cancer

Most sexually active people will become infected with human papillomavirus (HPV) at some point in their life, and most clear it without even realizing it. Among the women with the virus, however, some will develop cervical lesions. Gynecological examinations can detect these and they can be treated, if they worsen, so they are eliminated before they become cancerous. The whole process may take around ten years. Ten years, or more, in which the disease can be prevented.

Mauricio Maza is medical director at Basic Health International, an organization dedicated to fighting cervical cancer. He works in El Salvador, a country in which cervical cancer is more common and causes more mortaluty than breast cancer. “Cervical cancer attacks the poorest women, those who don’t have access to tests,” he explains. Women who do these checks can detect and control the disease in time. “It’s very rare for it to happen to someone who has resources, because she can follow-up on her treatment.” And that means that we do not see famous women, on television or in magazines talking about cervical cancer the way that they discuss breast cancer.

The data pack him up. The countries with the highest estimated mortalities for cervical cancer are the poorest. Of the 194 states reviewed by the World Health Organization (WHO), 66 had introduced the vaccine into their vaccination schedules by 31 December 2015. They are not the ones with the worst cervical cancer problems. In the absence of foreign aid, the countries that lack the means to pay for routine screening cannot pay for routine screening cannot pay for vaccination, either.

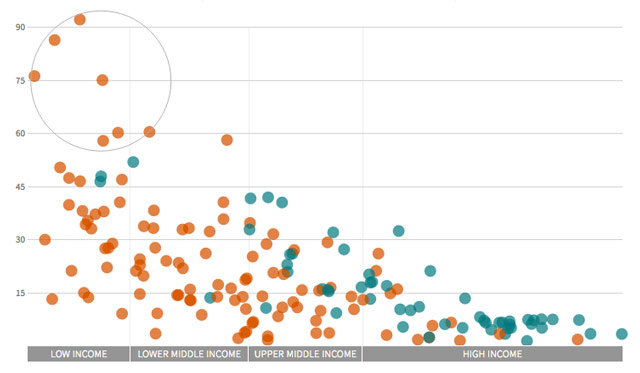

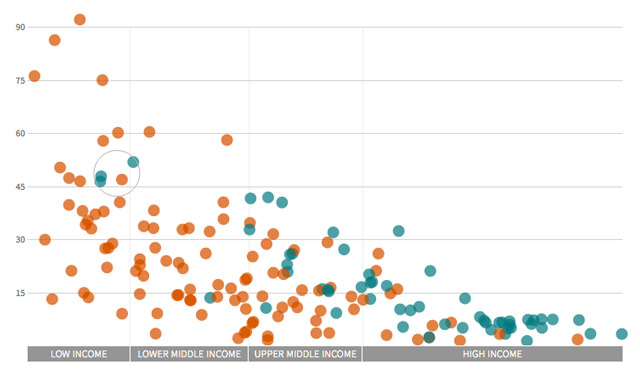

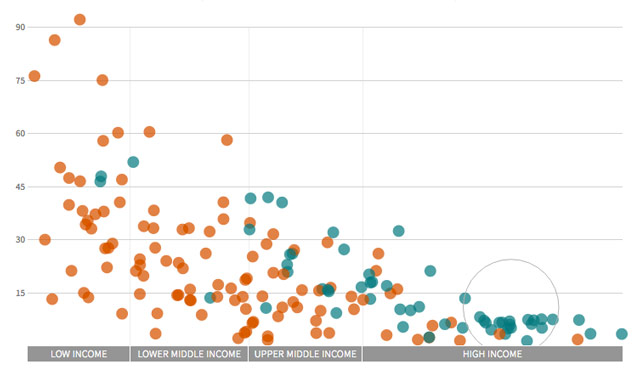

Deaths due to cervical cancer in 2015

Estimated deaths per 100,000 women ages 30 and over versus GDP of the country

- Countries vaccinating (as of end of 2015)

- Countries not vaccinating (as of end of 2015)

- Low income

- Lower middle income

- Upper middle income

- High income

deaths

per 100,000 women ages 30 and overVaccine included in public programme (as of end of 2015) Vaccine not included in public programme (as of end of 2015)

per 100,000 women ages 30 and over

Countries with highest mortality from cervical cancer are also the poorest and had not introduced the vaccine by 2015

Only a few low-income countries had introduced the vaccine in their programmes, thanks to GAVI's external assistance

Most countries that have the vaccine in their programmes are rich countries with low mortality from cervical cancer

There is another way to read the data: the vaccine is being introduced where it’s least necessary, in countries with the lowest incidence and mortality from the disease. “Sometimes people criticize that it’s being implemented in countries that need it less. Yes, but sometimes you need to do it where things are better organised, where a serious case with side effects detected can be analyzed… so that the others will grow convinced,” answers Mireia Díaz, a cervical cancer prevention, impact and cost analysis specialist at the Catalan Institute of Oncology.

Current vaccines are not the “complete solution”, Díaz points out. They don’t replace screening. They don’t reach everybody and while they protect against virus types that cause over 70% of cervical cancer cases, they do not protectagainst all virus types.

The main barriers to implementating of these new vaccines, according to a 2013 WHO report, are: the difficulty of reaching unschooled girls (the vaccine is recommended for girls between 9 and 13 years), the cost (the report asks for the price to be reduced to less than five dollars per girl vaccinated) and “rumors or misinformation” that can slow down implementation if the reasons for addressing only girls are not communicated. At this point, the report stresses that it’s very important to educate men also.

Social and cultural barriers

“Almost every week someone asks me whether or not to vaccinate their daughter, and these doubts come from religious, cultural issues… In many cases they believe that if they vaccinate their daughters they are telling them that they can start having sex, since HPV is a sexually transmitted infection,” says Mauricio Maza.

That is because this is not an ordinary vaccine. It is new, and related to a sexually transmitted virus. Nor is cervical cancer is not just any cancer: it affects only women.

Machismo and poverty slow down checkups and increase incidence

Video: Manuel Penados.

The Women’s Health and Development Instance is carrying out a screening program in several municipalities in Guatemala, attempting to circumvent cultural barriers by having women do the checkups themselves. They are trying this in Tecpán, for example, a municipality with a 90% indigenous population about two hours by car from the country’s capital. Most women agree to get tested, but “they are sometimes afraid of getting hurt,” explains Julia, one of the nurses who works at the health center. Many women hardly know their own bodies. Some indigenous languages lack a word for vagina. “If you feel it and it doesn’t hurt, there it is,” explains Celeste, who also works on the program. Most women going through screening had not been tested before. They are over 30 years old.

Sexual and cultural taboos join forces with anti-vaccine movements and organizations that question the safety and effectiveness of this new immunization. In 2014, the deputy minister of health of El Salvador affirmed, according to the national press, that the vaccine had not been introduced in the country’s immunization program due to the “serious side effects” detected in other countries. A local expert corrected him.

In a similar vein, Gloria Cruz, one of the civil society participantsat the Sexual and Reproductive Health Board of El Salvador, a meeting point between government, experts and organizations, admits that there are many doubts about the vaccine in the association she represents: “We do not have a clear position yet. We are informing ourselves.” In her view, the introduction of this vaccine into public health systems could mean a new case of what she calls “commodification of health.”

José Jerónimo, a specialist in cancer in women at the international nonprofit PATH, believes that these reservations are only temporary: “It’s typical of stages where something new is being introduced into the programs. It’s only a matter of time, the waters will calm down as we have more experience with the vaccine…”. Mireia Díaz reinforces this idea: “There are millions and millions of girls vaccinated in Europe, not one case of negative sife effects has ever been proven that was actually caused by the HPV vaccine. There is no evidence that this vaccine is harmful.” In 2009, after two 14-year-old girls were hospitalized with seizures in Spain, the European Medicines Agency defended the safety of the vaccine, claiming that a link between the seizures and the immunization was “very unlikely”. “Vaccination should continue,” the agency said.

The economic barrier

When the vaccine is not included in public programs, the only way to access it is through private clinics. Gerson Eduardo Gálvez Torres is a gynecologist at Aprofam, a Guatemalan network of not-for-profit clinics that offers affordable sexual and reproductive health services. He says few people ask for the vaccine. “Once you overcome the first barrier, the cultural one, the economic one stops you.”

Three types, two laboratories

Two laboratories produce the vaccine against HPV, which causes cervical cancer, among others: Merck (Gardasil) and GSK (Cervarix). The latter protects against HPV infections caused by types 16 and 18. Gardasil4, on the other hand, is tetravalent and protects also against types 6 and 11, which cause warts. A new version, Gardasil9, extends protection to nine virus types.

Not all clinics in Guatemala offer the vaccine. In many cases, you have to ask for it in advance. Among those who offer it, prices range from €100 to €200 per dose, and in most cases three are needed. Guatemala’s minimum wage is 86.9 quetzales per day, about €11.2, which means that a full immunization costs at least 27 days of minimum wage salary. These prices are very close to private sector prices in countries with much higher income such as Spain (€121.81 for Cervarix and €155.91 for Gardasil in pharmacies) or the United States (€183 per dose for 9-valent Gardasil for children, although in a package of ten doses). “Most people can’t handle these amounts,” stresses Dr. Gálvez.

And for the moment this is the only way. Neither Guatemala nor El Salvador have included the vaccine in their national immunization programs. “There is no budget for the basic stuff, much less for this which is a projection into the future,” says Gálvez, with resignation. According to Rodolfo Zea, deputy minister of health of Guatemala, “the target population is very large and the vaccine is very expensive.” That is why, although they plan to, they haven’t included it for now. The same is true in El Salvador. Eduardo Suarez, director of their immunization program, says they would need an investment of “about five million dollars,” which would mean 30% of the current national budget for all vaccines. “We know that the vaccine is necessary, but there are other activities that are a priority,” he admits.

Both countries could acquire Cervarix through the Revolving Fund of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) for about eight euros per dose. Although it is a lower price than is usually offered to countries that negotiate and buy alone, it’s not low enough for them and is almost double what the Gavi alliance, designed to provide for the poorest: €4.3 for Cervarix and €4.2 for tetravalent Gardasil.

The papilloma vaccine is one of the newest and most expensive on the market. The United States purchases the most advanced version of Gardasil, which protects against nine types of virus, for between €109.6 and €125.7 per dose, depending on whether it’s for children or adults. Merck sells the 4-valent version for €22 to Portugal and €14.5 to MSF. Spain buys both brands at the same price: €29.16 per dose. According to estimates from the last procurement contract, that would mean Spain will spend almost seven million euros per year until 2020.

In 2008 and 2009, a series of studies analyzed the cost effectiveness of the vaccine in different countries of the world. One of them focused on Latin America. Mireia Díaz, one of the authors, explains that most studies were intended to inform Gavi of which price would make it affordable and effective for countries to enter their program - with 78 members currently. According to her report, for the 2-valent vaccine to be cost effective in the 33 countries analyzed, full vaccination of a girl should cost less than $25. But for it to be accessible, those costs must fall. The research found that the HPV vaccine provides similar health value per resources invested as other new vaccines such as the rotavirus vaccine.

Adolfo García Montenegro, a gynecologist with expertise in cancer and specialist in the HPV vaccine, has a clear view of its advantages, especially in a country in Guatemala, where cancer treatments are expensive and do not reach the poorest population: “It’s much more expensive to treat a woman with cancer than to give her three shots. What happens is that there is no money for vaccines and there is no money to cure them either.”